Summary

The brightness evaluation method has become more and more important in the evaluation of road lighting, but the calculation work on brightness is very scarce. Although the road surface reflection table r(β, γ) provided by CIE (International Commission on Illumination) can calculate the brightness distribution of the road, the actual calculation process is difficult. The fundamental reason for analyzing the difficulty is that the road brightness distribution is based on Cartesian coordinates and the CIE reflection table is based on spherical coordinates. This paper introduces a new road surface reflection table based on Cartesian coordinates, called the r (x, y) table. Using the r(x,y) table to analyze road surface reflection characteristics will be more intuitive, visual and more systematic, and it is easier to calculate the linear road brightness distribution. In this paper, the method of guiding r(x, y) is given. The variation of reflection coefficient in the direction of road and vertical road is analyzed in detail, and the calculation is conveniently calculated by r(x, y). A method of brightness distribution for a single lane and the entire road. This will greatly facilitate the analysis of how the brightness of the road is given for a given luminaire, and how to design a luminaire with an equal brightness distribution.

Among the evaluation methods of road lighting, the brightness evaluation is more appropriate than the illumination evaluation, especially for the illumination of highways. This is because the brightness depends on the driver's observation, which is closely related to road traffic accidents, and the illumination is only measured by the instrument. In many countries, brightness evaluation has been the main method for road lighting quality evaluation [1-3], and the calculation of brightness has become more and more important in road lighting.

Compared with traditional luminaires, LEDs can easily change their light intensity distribution with various lenses, so LED road lighting can achieve accurate light intensity distribution, thus achieving higher road illumination brightness uniformity while at the same time meeting A certain illuminance uniformity to meet the requirements of certain road lighting standards. This realistic possibility greatly increases the need for road lighting engineering to first satisfy a uniform brightness distribution rather than a uniform illumination distribution, which also increases the requirements for the calculation of the road illumination brightness distribution of LED lamps. However, due to its complexity, this calculation was a technical weakness in the past. The analysis of the illumination brightness distribution can only rely on the commercially available lighting software. The analysis of these software can only have limited results, and it cannot be pressed. The designer's request is analyzed. There have been very few articles on the calculation of the brightness distribution in road lighting. The goal of this paper is to improve the calculation method of road brightness distribution, so that it is more convenient to design LED lenses with equal brightness distribution.

1 difficulty in calculating road brightness distribution

The brightness of a road is related to many factors, including the type of road surface, the direction of the light, the position of the observer, and the direction of the observation. In order to standardize the calculation of the brightness distribution, CIE (International Commission on Illumination) and PIARC (International Association of Road Conferences) stipulate standard pavement and standard observation conditions [3-4], which makes the brightness calculation standard. Thus, the brightness L at the determined point can be calculated by the following formula:

Here I (θ) is the light intensity distribution of the luminaire, H is the installation height of the luminaire, and the sum includes all the luminaires that can be shot at this point. C is constant for determining the road. Since this paper only cares about the relative brightness, we do not have to give C value.

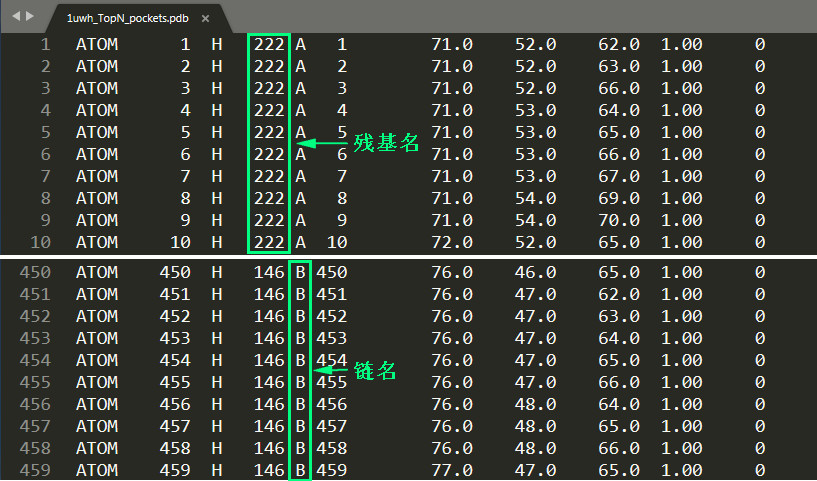

The variable r in equation (1) is called a simplified reflection coefficient and is a function of β and γ. As shown in Fig. 1, β is the angle between the incident surface and the observation surface, and γ is the vertical angle of the line with the perpendicular and the light. The simplified reflection coefficient table, also called the reflection table, is represented here by r(β, γ), which is the r(β, γ) table of the R3 road surface published by CIE [4-5].

Using the r(β, γ) table provided by CIE, equation (1) can be used to calculate the road surface brightness [2, 3, 8]. However, it is very difficult to use r(β, γ) to calculate the road which is usually in Cartesian coordinates. Moreover, considering that r(β, γ) gives only the brightness contribution caused by a luminaire at a certain point on the road, the brightness distribution of one lane must also evaluate the sum of the contributions of the lamps at each observation point, plus the road More than one lane, it is conceivable that calculations will be very difficult. The computational complexity is also the reason why articles with few brightness calculations appear.

.jpg)

2 A new method for calculating road brightness distribution

The basic reason for analyzing its computational complexity is actually the inconvenient calculation of the angular relationship in Cartesian coordinates. This paper first proposes that this problem can be solved in a straight road. We will demonstrate below that all lamps on a straight road have the same height, the same lamp spacing, and the same intensity distribution, which can introduce a new reflection that depends only on the coordinates x and y instead of β and γ. coefficient. This new r(x,y) table will give its introduction method in Section 3. Here, the results are given in advance. Table 2 is the R3 road surface and the 10m lamp height as an example of r(x, y). table.

The origin of the coordinates of Table 2 is located directly below the luminaire, with the x direction pointing in the direction of the road and the y direction being perpendicular to the road. Considering that the forward reflection coefficient is greater than the backward direction, the value of the x direction along the road in Table 2 is 150m forward 50m, and the y direction perpendicular to the road ranges from 0-12m.

In this way, for a road brightness with a fixed lamp height on a straight road, a simple arithmetic operation can be used to obtain a brightness distribution. Readers can use the methods in Section 3 to import their own r(x,y) tables of different lamp heights and use them for further calculations.

3 introduction method of reflection coefficient r (x, y) table

In order to avoid loss of precision in processing, we first interpolate the r(β, γ) table, and linear interpolation with five nodes can guarantee accuracy. This results in a more accurate r(β, γ) table with small steps. However, this table still uses β and γ as independent variables, which is not the table we want. The specific results are not given here.

Then, give an r(x,y) "empty" table whose x and y range and step size are as we gave in Table 2. Since the type of pavement, the height of the lamp, and the spacing of the lamps are known at this time, the x and y values ​​of each cell in Table 2 are also fixed, so β ​​and γ of each point are also known, and no additional calculation is required. The reflection coefficient at the r(x, y) point can be obtained from the reflection coefficient in the interpolated r(β, γ). Since the r(β, γ) after interpolation is more accurate than the original, r(β, γ) table, the obtained r(x, y) table also has sufficient accuracy. This process is also a tedious task, but this is a work that is once and for all. The type of pavement and the height of the luminaire are limited. Therefore, the number of r(x, y) that needs to be calculated is also limited. We do not need to give a detailed calculation process here, but only the calculation results of the lamp height of the R3 road surface l0m are given in Table 2.

It must be stated that the r (β, γ) table given by the CIE is the authoritative raw data and is the standard data obtained from the actual measurement. The new r(x,y) table uses this raw data to process straight roads, but this processing is not just a mathematical coordinate transformation. In fact, the introduction of the new r (x,y) table brings Unexpected benefits, as you can see below, make it easy to analyze road reflections and make calculations easier and more intuitive.

4 Analysis of pavement characteristics by r(x, y) table

4.1 3D general map of the r(x, y) table of the R3 pavement

Since the r(x,y) table is in the Cartesian system, this makes it easier to draw a 3D map of r(x,y), which was previously difficult. Figure 2 shows the 3D graph of the r3 road r(x,y) table. The x and y in the figure are the coordinates of the road, and the reflection coefficient distribution of the straight road can be clearly seen from the figure. This picture contains the entire reflective nature of the road, which is an exciting result, and initially saw the superiority of introducing the r(x,y) table.

4.2 Reflection coefficient of R3 pavement y=0 lane

Figure 3 shows the reflection coefficient at the y = 0 of the R3 road surface. In fact, Figure 3 is a line of Figure 2, but it contains all the data needed to calculate the luminance distribution on that lane with y = 0. The peak of the curve in Figure 3 is not at y = 0 but near x = 12. Moreover, the curve attenuates to the right and decays slowly to the left. This means that for the same distance to the same luminaire, the forward light (the light from the x>0 lamp) is reflected more than the backward light (the light from the x<0 lamp). This also means that when calculating the road brightness distribution, the light in the far side is also contributing to the light behind the rear. For the lamp spacing of 30m on the R3 road surface, it is known from the analysis of Section 5.2. When calculating the brightness of a certain point on the road surface, it is generally necessary to take 4 lamps to the front and then to 1 lamp.

.jpg)

On the other lanes with y > 0, the values ​​of the curves are different but their tendency is similar compared to Figure 3.

4. 3 relationship between reflection coefficient and pavement material

The r ( x, y) table for pavements of different materials can be obtained in accordance with the method in Section 2. For example, the R-Series pavement contains four pavement types: R1, R2, R3, and R4. Figure 4 shows the variation of r ( x,0) for the four types of R-series.

From Figure 4 we can get a valuable conclusion that the pavement material has a great influence on the reflection coefficient, and the directionality of the R1 and R2 pavements is not strong (the difference between the forward and backward directions is not large), while the R3 or R4 pavement is not. Has a strong directionality.

With the r ( x, y) table, the variation of the reflection coefficient perpendicular to the direction of the road is also easy to obtain. Figure 5 shows the variation of the R pavement series in the direction perpendicular to the road r ( 12, y). The four curves have similar trends with y, but the value of R1 is larger, which provides the basis for brightness analysis perpendicular to the road direction.

.jpg)

5 Calculate the brightness distribution using the r ( x, y) table

5.1 Single light intensity distribution

Using the r ( x, y) table can greatly simplify the calculation of the brightness distribution on a straight road. Consider the brightness distribution on a lane first. Figure 6 shows an example of the I ( θ) distribution of a luminaire in our design. It is not difficult to give a mathematical expression of I ( θ), which can be obtained by graphical simulation or by describing the intensity distribution of the luminaire. The IES file is obtained, and we will not give its specific mathematical expression here. With the I ( θ ) distribution, the luminance distribution can be calculated using equation ( 1).

I ( θ ) in polar coordinates can easily be changed to I( x) in Cartesian coordinates. The relationship between these two independent variables is:

The graphic display of I ( x) in Cartesian coordinates at 10 m lamp height is shown in Figure 7.

5. 2 single lane brightness distribution

Since the brightness is proportional to the product of the reflection coefficient and the light intensity, that is, the brightness on the road surface is r ( x, 0) I ( x) , that is:

The graph shows that this product is the curve of Figure 8. In fact, Figure 8 is the result of multiplying Figure 3 and Figure 7. This is the brightness distribution of a single luminaire on a single lane. Here the coordinates x are the distances the luminaire leaves the observation point. It can be seen from the figure that the contribution of the forward light (x > 0) is significantly greater than that of the backward light (x < 0). This is a result of how the brightness of a luminaire caused by the introduction of the r (x,y) table is distributed on a straight road. This is a very valuable result. As we will see below, we will not have it. It is difficult to get the brightness distribution of all the lights at all points on the road.

When the lamp spacing is 30m, it can be estimated from Fig. 8 that the fourth lamp (120m away) contributes only 2% of the maximum contribution to the brightness of the observation point. If the lamp spacing is reduced to 25m, the contribution of the fourth lamp It is also only 3% of the biggest contribution. In this way we can get important conclusions in the calculation of road brightness: just consider the positive direction of 4 lights in the direction of 4 lights. Considering that the R3 road surface is a road with strong reflection direction and the reflection coefficient at y ≠0 is smaller, this conclusion can be safely used for other roads and other lamp spacings in other lanes.

For a longer straight road, the brightness distribution between every two fixtures is the same, we only need to consider the range of a light spacing, as explained above, only need to consider 5 fixtures at each point. Now that we have Figure 8, we can more clearly use the graph to express the laws of the influence of these five lamps. Taking the lamp spacing of 30m as an example, the brightness contributions of all the observation points of the five lamps in the range of 30m between the two lamps are respectively shown in Fig. 9.

Adding the five lines in Figure 9 is the brightness distribution between the lamp spacings. The results are shown in Figure 10. The figure shows that the brightness uniformity of the single lane of this luminaire is about 91%.

The brightness distribution in the range of about 240m for the entire lane is shown in Figure 11. In fact, Figure 11 is the eight periodic repetitions of Figure 10. Fluctuations in the periodicity of the brightness can be seen in Figure 11, which is inevitable for pitch-type luminaire illumination, but the 10% fluctuation in the figure is relatively small. If there are serious fluctuations, a so-called "zebra crossing" that affects traffic safety will be formed. This zebra crossing is a result that can be calculated at the time of designing the luminaire for further analysis. The specific method is not described in this paper.

It can be seen that with the reflection table r ( x, y) in Cartesian coordinates, we can get the brightness distribution of the single lamp on the single lane as shown in Figure 8. Dividing this distribution into 5 segments, we get the brightness of the five contributing lamps in one dot spacing as shown in Figure 9. Adding these five curves yields a single-lane luminance distribution within a lamp spacing as shown in Figure 10, which is the luminance distribution of the entire lane. The above process of graphical representation is clear and coherent, and the complexity calculated by the r (β, γ) table in spherical coordinates is another important application for introducing the r(x, y) table.

5. 3 brightness distribution of the entire road

I ( θ) and I ( x) describe the intensity of a single lane. For a multi-lane road, the light intensity distribution of the luminaire can be changed to a function I ( x, y) using two independent variables. This style (2) should be changed to equation (3):

How do I get I ( x, y)? We already have a distribution of reflection coefficients perpendicular to the road surface. The results of the R3 road surface are shown in Figure 5. We can use this distribution as a basis for extending from I ( x ) to I ( x,y). Simply put, since r ( x, y) is smaller than r ( x, 0), if you want the brightness L of the road to be uniform across the road, only I ( x, y) is larger than I ( x, 0). . As a primary approximation, we can use equation (4) to find I ( x, y) :

In this way, the brightness calculation result of the above single lane can be extended to multiple lanes. It is not difficult to calculate the brightness distribution on the entire road with a simple program. Still taking the R3 road as an example, the results are shown in Figure 12, where the overall brightness uniformity is about 85%.

6 discussion

1) In this paper, the reflection table r (β, γ) of CIE is transformed into the r (x, y) table in Cartesian coordinates. The result is consistent with the road coordinates. The effect of this transformation makes the calculation of road brightness very convenient.

2) Some brightness distributions can be performed using commercial software, but commercial software has limited limitations, no digital results, and cannot be changed according to user needs. Compared with commercial software, the analysis of brightness is more vivid, systematic and in-depth, and more practical graphical results can be obtained. Moreover, the quantitative calculation method of this paper is not difficult for ordinary designers to master.

3) The premise of this paper is a straight road, but since most roads are actually straight, the results of this paper are very broad.

4) For different lamp heights, there should be different r (x, y) tables, but in fact the height of the lamps is only a limited number, such as 8m, 10m, because the method of this paper is easy for general optical engineering designers to master. You can use programming to simplify the calculation process, so this does not have a big impact on the design.

5) It is easy to calculate the brightness of the road, so that the light intensity distribution of the LED can be easily modified to obtain the brightness distribution required by the designer. With the light intensity distribution, the shape of the lens can be calculated by the method of [9]. This will greatly speed up the design process of lighting fixtures with equal brightness distribution. This will be a more important application, but the content is beyond the scope of this article.

references

[1] ANSI. American National Standard Practice of Roadway Lighting. ANSI / IESNA RP - 8 - 00, 2005.

[2] MOHURD.Standard for Lighting Design of Urban Road: CJJ 45-2006.

[3] CIE. Lighting of Road for Moto and Pedestrian Traffic, CIE publication N0. 115, 2008.

[4] CIE.Road Surfaces and Lighting.CIEpublicationN0.66, 1984.

[5] CIE.RoadSurfaceandRoadMarkingReflection Characteristics.CIE publication No.144, 2001.

[6] BSEN 13201-3 Road Lighting Part3 Calculation of performance. 2003.

[7] FENGZexin, LUO Yi, HAN Yanjun. Design of LEDfreeform optical system for road lighting with high luminance /illuminanceratio.Opt.Express,2010,18( 21) : 22020-22031.

[8] CIE.Calculation and Measurement of Luminance and Illuminance in Road Lighting. CIEpublication N0.30-2, 1982.

[9] Zhou Shikang, Chen Chungen, Xu Li, et al. Luminous flux line method for LED secondary optics design[J]. Journal of Lighting Engineering, 2016, 27(1): 101.

Tinned Copper Clad Copper TCCC

Corrosion-Resistant Copper-Clad Tinned Wire,Copper-Clad Copper Tinned Wire Production,Copper-Clad Copper Tinned Wire Processing,Copper-Clad Tinned Wire

changzhou yuzisenhan electronic co.,ltd , https://www.yzshelectronics.com